Midlife Crisis Meaning: James Hollis’s The Middle Passage

One of the most influential books on the mid-life crisis, and the broader topic of adult self-development is The Middle Passage: From Misery to Meaning in Midlife, by Dr. James Hollis.

A Jungian psychologist, Dr. Hollis integrates and builds upon many of the teachings of 20th century Psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, or C.G. Jung, and his work on the shadow self and unconsciousness.

In The Middle Passage (Dr. Hollis’s reframed term for the midlife crisis), Dr. Hollis not only examines the causal factors and consequences of the mid-life crisis, but also offers ample insight into how to navigate the mid-life crisis, while providing a wealth of encouragement for anyone going through a mid-life (or other life stage) crisis.

This essay offers my own paraphrased interpretation of the key takeaways, along with direct quotes and questions raised drawn from Dr. Hollis’s seminal book on deriving meaning and answers from the mid-life crisis.

Part 2 will be a deep dive into the main themes raised throughout the book.

Key Takeaways

“The experience of the middle passage is not unlike awakening to find that one is alone one a pitching ship, with no port in sight. One can only go back to sleep, jump ship, or grab the wheel and sail on… In grabbing the wheel we take responsibility for the journey, however frightening it may be, however lonely or unfair it might seem. In not grabbing the wheel we stay stuck in the first adulthood, stuck in the neurotic aversions which constitute our operative personality, and therefore our self estrangement. At no point do we live more honestly or with more integrity than when, surrounded by others yet knowing oneself to be alone, the journey of the soul beckons and we say yes to it.”

Dr. Hollis uses the above metaphor (attributed to a character in a play by Christopher Fry) towards the end of the book in order to describe the terrifying and exhilarating experience of traveling through the mid-life crisis, or as Dr. Hollis calls it, the “Middle Passage.”

Throughout the book, Dr. Hollis references, explains, and explores the following 3 key themes (the first of which is attributable to Dr. Hollis and the following 2 of which are central themes in Jungian psychology) and their effects in relation to adult development and The Middle Passage.

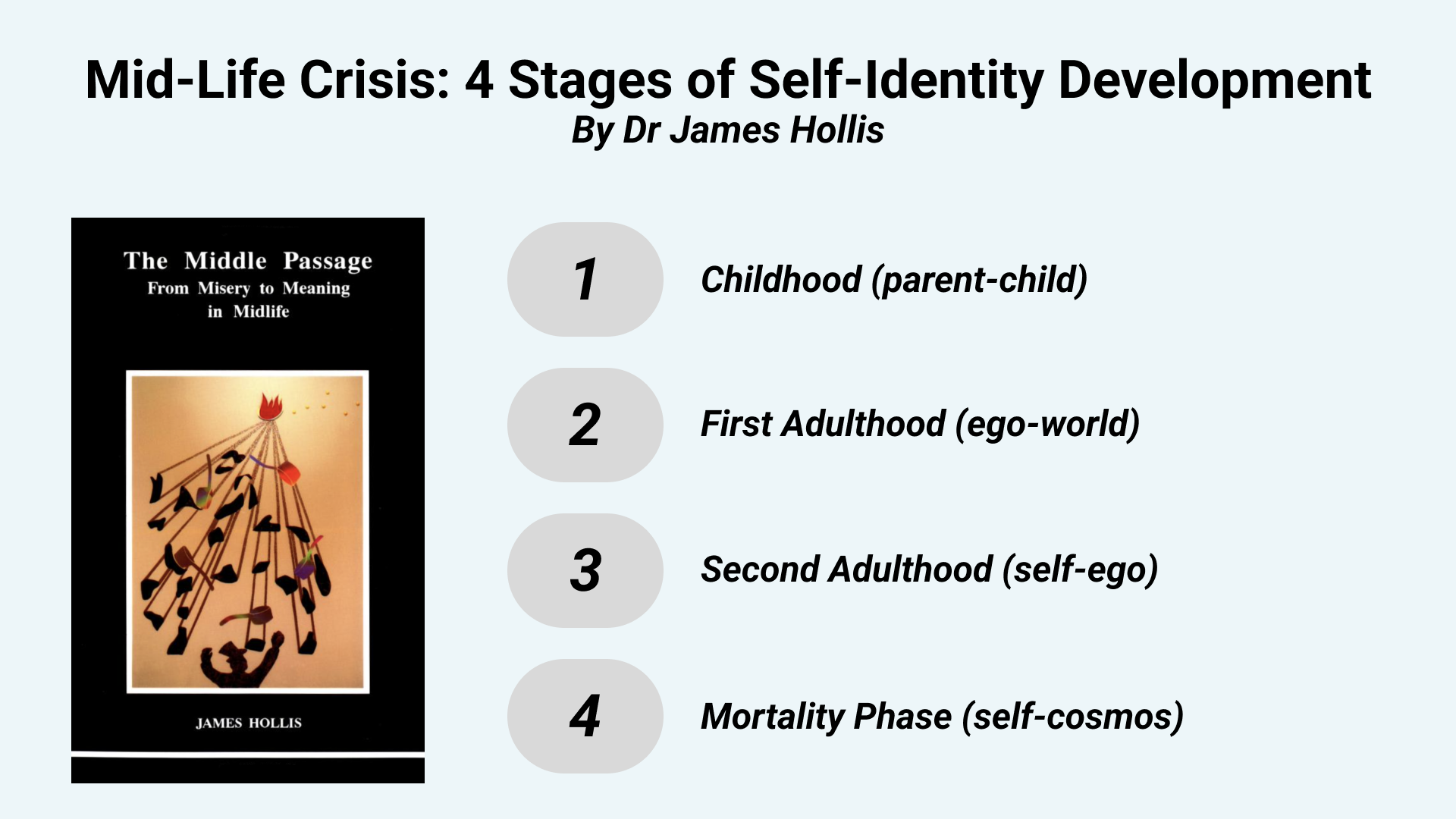

The 4 stages in the continuum of self-development, from the first half of life (the childhood and first adulthood phases), and moving on to second half of life (the second adulthood and mortality phases).

The unconscious, or shadow self (a collection of ego-repressed parts of ourselves), and the projection of the contents of the unconscious or shadow self into conscious form in one’s life.

The influence of society and the parental role on ego development, and consequently the contents of the unconscious/shadow self.

From Dr. Hollis’s work, an important point to understand is that the formative years of one’s self-development (the childhood and the first adulthood or adolescent phases), many aspects of one’s outward self come to be interpreted by the developing ego as undesirable, on behalf of the powerfully influential external sources in one’s life; namely parents and society. In response to such judgments of the outward self, the ego (which has the role of modulating and urging pursuit of an ideal vision of self) attempts to “split off” or rid the core self of such negatively judged parts, in order conform to the ego’s ideal vision of self (see Lawrence Kohlberg’s stages of moral development to explore more of what is defined as “ideal” at different self-developmental stages).

The ego attempts to accomplish this self-management goal by “splitting off” of parts of one’s core self, and pushing (or repressing) these split-off parts into the unconscious, or “shadow self,” away from the core self’s conscious awareness. These parts include aspects like non-affirmed characteristics of the core self, insecurities, society-denied urges, and traumas. The ego’s drive to selectively repress the core self’s aspects causes one’s unconscious to become filled over time with such parts, which contradict the ego-aspirational vision of self. The more intense the negative judgement attached to these parts, the deeper into the shadows they are pushed.

Despite the efforts of the ego to rid the core self of these undesirable parts, these now-unconscious, shadow self-aspects nevertheless do not disappear, and instead exert an invisible (or more accurately below conscious awareness) influence on the conscious core self’s decisions, desires, expectations, and other thought patterns through a process known as “projection.”

An example of an unconscious-influenced projection might be a heterosexual individual’s decision to pursue romantic relationships with partners who are either extremely alike (or extremely unlike) that individual’s opposite-sex parent, due to an unconsciously-repressed hatred of that parent.

Due to their repressed nature, decisions influenced by unconscious projections are (without the illumination of psychological analysis) invisible at the level of one’s conscious awareness. Like a chair being carried across a room by an invisible pair of hands, without an explanation, the core self would be quite confused and distracted by the floating object.

This presents a problem for the ego, which can only repress, but cannot fully be rid of the shadow self aspects. The ego, then must consciously account for the source of such influences (i.e. invent a reason for why the chair is floating across the room), in order to maintain a semblance of control over the core self’s actions. So, the ego resorts to another core-self deception, by conjuring rational-sounding reasons in order to veil the unconscious source of projection-influenced actions. The ego then pressures the core self into believing such narratives, so that the core self will not realize that the undesirable parts did not actually disappear, but were only migrated out of view by the ego. Such a revelation would, after all, invalidate the ego’s efforts to make undesirable aspects of the core self disappear and would destroy the ego’s status as the credible guide in enabling the core self to reach the ego-ideal vision of self.

For as much trouble as the ego’s machinations stir up, Dr. Hollis grants that the ego does serve a very important purpose in the self-development continuum: “without a sufficiently strong ego, we would not have the strength to leave our parents and venture into the world.”

The ego is an essential mental structure that powers the shift from identity development stage 1 (childhood and parental dependence) to developmental stage 2 (the first adulthood and the core self’s first ventures into establishing an individuated presence in the world, by way of the ego-world axis).

An overpowered ego transforms from becoming an engine of self-development to a serious obstacle if the ego convinces us to remain in stage 2, where we (the core self) look only to the world to give us our sense of self and meaning.

That said, as we age, the ego’s semblance of wool covering over reality naturally begins to fray in the face of the challenges and limitations, particularly those presented at midlife.

For example, an individual may have pursued a path as a doctor, lawyer, or business person, as driven by the ego’s logic that such a job is what that individual actually wants or needs, yet influenced by an underlying unconscious insecurity of not being accepted by parents or society without having such a job. At midlife, this projection may collapse, when the core self comes to the conclusion that the individual is still not happy, and on top of that has also wasted years pursuing that career without the expected results, despite the ego’s persistent rationale that such a path would indeed lead to happiness.

Other examples might include an individual’s unconscious desire as a parent for their child to fix their own feelings of failure in life, an individual’s hope that a romantic partner will constantly fulfill their need for validation, or the sense of loss of security as one’s physical health/appearance degrades.

Dr. Hollis explains that The Middle Passage arises with the collapse of projections that had been previously assumed would resolve our internal insecurities. The collapse of projections is essentially a “witnessing the death of one’s sense of self through previously seemingly stable projections.”

When our projections collapse, it can be a terrifying and extremely disruptive realization, and it is natural to fall into depression, fear, anger, denial, or acting out as initial reactions to this process. Yet, if we attempt to rebuild or find a new external aspect to project our hopes/fears upon, we will not discover the opportunity of resetting our self identify on the far more stable, ego-transcendent axes. We will continue to be in a repeating cycle of running from our insecurities by projecting such shadow contents onto elements of life that inherently cannot resolve such insecurities. So long as we avoid doing the work to integrate our insecurities, they and our ego will continue to unconsciously drive us to define our self identity via our external, worldly interactions, which puts us at constant risk for devastation of self-identity.

It is the collapse of our naive assumptions that something out there in the world will save/fix/heal that gives us the opportunity to mature; to go inward and examine the source of the hopes/fears, and come through this Middle Passage with a more realistic self-awareness.

Dr. Hollis also points out that creating and maintaining our projection defenses also takes up an enormous amount of our energy and focus. When we withdraw these energies from the act of projecting, we free up a tremendous amount of energy for other pursuits in our self-development.

Dr. Hollis summarizes that, “as painful as the encounter with our shadow may be, it reconnects us with our humanity. In the midlife passage, we face an appointment with what is within our shadow selves.”

The action we must take is clear for Dr. Hollis: “we must take full responsibility for our physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being, without attempting to project these responsibilities onto the world and others in the world. We must let go of the illusion that we know who we are and are in control, which is ego supremacy.”

We successfully navigate through the Middle Passage when we have delved into our shadows and come into understanding and alignment with (integrated), our whole selves that the ego spent the first adulthood splitting up and repressing. When we no longer give the world the power to define us or make us feel okay, or secure. When we internalize our decision-making authority as a stable, core self, and gain greater awareness of our future projections. When we no longer expect the roles we play, or our job or relationships to heal our broken parts. When we accept that nothing can give us certainty in life, control over the perception of others, or the ability to prevent decline and death, and when in the face of such disappointments, we choose to turn the other cheek, and stride bravely into the remainder of our lives.

Powerful quotes from The Middle Passage

“We must separate who we are from what we have acquired… I am not what happened to me, but what I choose to become.” – James Hollis

“We are in the middle passage when the magical thinking of childhood and the heroic thinking of adolescence are no longer congruent with the life one has experienced. Once we have experienced ample disappointment, heartache, the collapsing of projections of hopes and expectations, experienced the limitations of talent, intelligence and the limitations of courage itself.”

“We must find a balance between our job – earning a living – and our vocation – our calling. We must ask, what am I called to "do? And then we must do it.” – James Hollis

“Our capacity for growth depends on one’s ability to internalize and take personal responsibility.” – James Hollis

“For every aspirant on the career leader is a burned out executive who longs for a different life.” – James Hollis

“When increasing pressure from within becomes less and less containable by the old strategies, a crisis of selfhood erupts. We do not know who we are really, apart from a social role and psychic reflexes. And we do not know what to do to lessen the pressure. Such symptoms announce the need for a substantive change in a persons’ life. Suffering quickens consciousness, and from consciousness new life may follow.” – James Hollis

“Wheresoever we find wounds, deficits in our history, there we are obliged to parent ourselves.” – James Hollis

“At midlife, we must also let go of our experience of how our parents’ relationship with each other affected our own capacity of intimacy.” – James Hollis

“The more individuated the parent, the more free the child can be. The same freedom we wished to become our parents would bestow upon us, we must grant to our own children.” – James Hollis

“Letting go of children during our middle passage is not only helpful for them and necessary for us, since it releases energy for our own further development.” – James Hollis

“The general psychological reason for projection is always an activated unconscious that is seeking expression… Projection is never made, it happens. It is simply there.” - Carl Jung

“I have frequently seen people become neurotic when they content themselves to inaccurate or wrong answers to the questions of life. They seek position, marriage, reputation, outward success or money and remain unhappy and neurotic, even when they attain what they’ve been seeking. Such people are usually confined within too narrow a spiritual horizon. Their life has not sufficient content, sufficient meaning. If they are enabled to develop into more spacious personalities, the neurosis generally disappears.” - Carl Jung.

“A neurosis must be understood ultimately as the suffering of a soul which has not discovered its meaning.” – Carl Jung

“The price of civilization is neurosis.” – Sigmund Freud

Key questions to ponder from The Middle Passage

Who am I beyond my history and the roles I’ve played?

Who am I, if I am not my ego and not my complexes?

What work then needs to be done given what I am learning?

What meaning ought a relationship to have if it’s not going to deliver on the expectations of the inner child?

How can our partner/romantic relationship help us find meaning?

What do I want?

What do I feel?

What am I called to do?

What must I do to feel right with myself?

That’s all for today – thanks for reading! Learn more about how working with a personal development coach can help you to live a more fulfilling life, sign up for my newsletter, and stay tuned for more self-discovery essays.